Understanding that Paradox was the “straight woman” helped me see character archetypes clearly. But knowing Patricia was a Fool and Kevin was a Chaos Agent didn’t explain why they generated laughs while my early attempts at “quirky” characters fell flat.

Then I noticed a pattern. Every successful comedy character – from Dwight Schrute to Gilfoyle in Silicon Valley – operates on the same three-part framework. It’s not about being weird or random. It’s about having a consistent internal engine that generates comedy naturally.

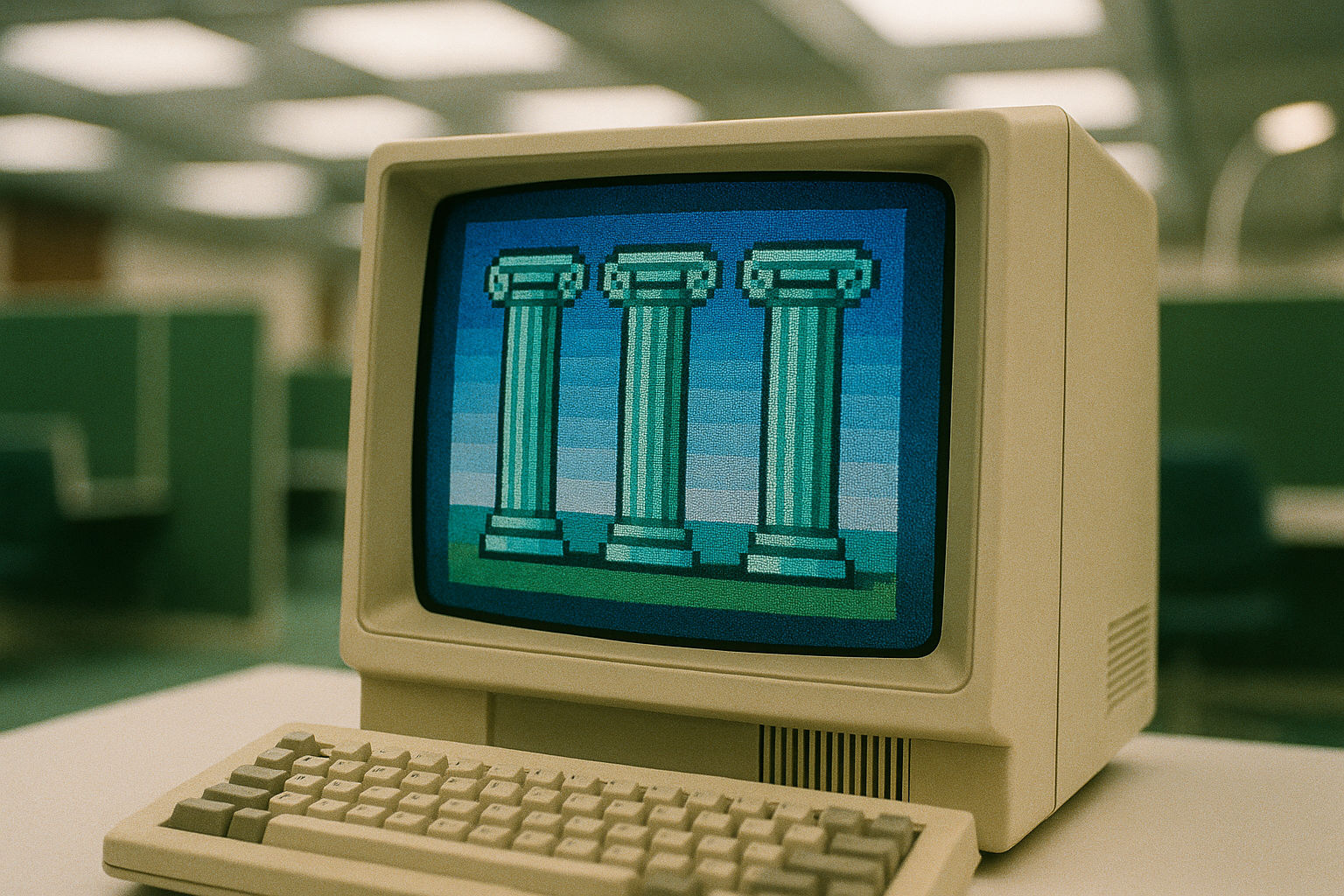

The Three Pillars of Character Comedy

After analyzing what made certain characters consistently funny, the pattern became clear. Every memorable comedy character has:

1. Obsession: What They Care About Too Much

This is your character’s north star – the thing they value above all else, often to irrational degrees. It’s not just something they like; it’s something that drives their decisions even when those decisions make their life worse.

Patricia’s Obsession: Creating perfect workplace wellness She doesn’t just think wellness is nice – she believes it’s the solution to every problem. Server crash? We need better work-life balance. Budget crisis? Time for a meditation retreat. Her obsession blinds her to actual cause and effect.

Kevin’s Obsession: Proving his old methods still work Kevin doesn’t just prefer PHP – he’s built his entire identity around being the guy who’s kept sites running since 2014. Every modern practice threatens not just his code, but his sense of self.

2. Blind Spot: What They Can’t See About Themselves

The blind spot is what everyone else can see but the character cannot. It’s not stupidity – it’s a specific gap in self-awareness that creates friction with reality.

Patricia’s Blind Spot: She can’t see that wellness doesn’t equal competence Patricia genuinely doesn’t understand why her aromatherapy diffusers don’t improve code quality. In her mind, happy developers naturally write better code. The fact that they need to actually know how to code doesn’t register.

Kevin’s Blind Spot: He can’t see that “working” isn’t the same as “good” Kevin’s code runs. That’s all the evidence he needs. The fact that it’s held together with globals, hasn’t been updated in seven years, and requires a full moon to deploy successfully? Details.

3. Coping Mechanism: How They Make Things Worse

When challenged or stressed, how does the character respond? The best comedy coping mechanisms escalate problems rather than solve them.

Patricia’s Coping Mechanism: Doubling down on wellness initiatives When her meditation session doesn’t fix the server issue, does Patricia reconsider? No. She schedules a weekend retreat. When that doesn’t work? Mandatory daily feelings circles. Each failure just proves we need MORE wellness.

Kevin’s Coping Mechanism: Adding more of what already works Someone questions Kevin’s approach? He’ll show them by adding another layer of his “proven” methods. More globals. More copied functions. More comments explaining why modern approaches are unnecessary. It’s like fighting a fire with gasoline.

Why This Framework Creates Sustainable Comedy

The three-pillar system creates what I call “comedy perpetual motion.” The obsession drives the character into situations where their blind spot causes problems, which triggers their coping mechanism, which creates bigger problems, which activates their obsession again.

Watch Kevin in action:

- Obsession activated: Someone suggests using version control

- Blind spot engaged: He can’t see why “I email myself backups” isn’t sufficient

- Coping mechanism triggered: Creates elaborate folder system with dates

- Result: Now nobody can find anything, validating his belief that simple solutions (his) are better

The cycle is self-reinforcing. Kevin never learns because each disaster just proves his point – in his mind.

Character Comedy vs. Situational Comedy

Here’s the crucial difference I missed in my early attempts:

Situational comedy asks: “What funny thing happened?” Character comedy asks: “How did this person’s nature make it funny?”

Take a server crash:

Situational approach: The server crashes at the worst possible time, maybe during a important demo. People panic, things go wrong, maybe someone spills coffee on the backup server. It’s funny because it’s chaotic.

Character approach: The server crashes, and:

- Patricia sees an opportunity to practice “crisis mindfulness”

- Kevin insists his manual backup system from 2014 would have prevented this

- Gabriel refuses to help unless they commit to open-source monitoring tools

- Paradox silently fixes it while everyone argues about whose fault it is

The situation is the same, but the character approach generates four different comedy threads that can interweave and escalate.

Building Your Own Character Engines

When I started developing secondary characters for Paradox, I used this template:

Step 1: Define the Obsession What does this character value more than anything? Not just professionally – what drives their worldview?

Step 2: Find the Blind Spot What obvious truth can’t they see? The best blind spots are related to their obsession – they can’t see the thing that would undermine their core belief.

Step 3: Design the Coping Mechanism When reality conflicts with their obsession, how do they protect their worldview? The funnier coping mechanisms make things worse while feeling logical to the character.

Example: Building Gabriel from Scratch

Early draft Gabriel was just “likes open source.” Boring. No engine.

Adding the Three Pillars:

- Obsession: Technical purity and “doing things right”

- Blind Spot: Can’t see that perfect is the enemy of done

- Coping Mechanism: Overengineering simple solutions to prove the “right” way

Now Gabriel doesn’t just prefer open source – he’ll spend three weeks building a FOSS alternative to a $5 service. When deadlines loom, he doesn’t compromise; he works harder to prove his approach is feasible. Every shortcut others take just reinforces his belief that he’s the only one who truly cares about quality.

The Evolution from Quirks to Engines

My early character attempts relied on quirks:

- “Kevin uses old code”

- “Patricia likes wellness”

- “Gabriel prefers open source”

These are just facts, not engines. They don’t generate comedy on their own.

The three-pillar framework transforms quirks into comedy engines:

- Kevin doesn’t just use old code – he’s obsessed with proving it’s superior

- Patricia doesn’t just like wellness – she believes it solves all problems

- Gabriel doesn’t just prefer open source – he sees proprietary software as moral failure

The difference is motivation and belief. Quirks are external. Engines are internal.

Why Characters Shouldn’t Learn

Here’s a hard truth about comedy: growth kills the engine. If Patricia realizes wellness doesn’t fix technical problems, she stops being funny. If Kevin modernizes his approach, the comedy dies.

This doesn’t mean characters can’t have moments of success or depth. But their core engine – their obsession, blind spot, and coping mechanism – needs to remain intact.

Paradox can grow and change because she’s the straight woman. Her comedy comes from reacting to others, not from her own engine. But the chaos agents need to stay broken in their specific, consistent ways.

Testing Your Character Engine

A well-built character engine should be able to generate comedy from any situation. Drop them anywhere and their nature creates the humor:

Patricia at a funeral: Suggests the death is an opportunity to practice grief mindfulness Kevin at a tech conference: Explains why every new technology is unnecessary Gabriel at a proprietary software company: Treats it like visiting a factory farm

If you can’t immediately see how your character would create comedy in random situations, their engine needs work.

The Framework in Practice

Looking at successful comedies, you’ll see this framework everywhere:

- Ron Swanson: Obsessed with self-reliance, blind to the value of government (while working in government), copes by doing less work

- Dwight Schrute: Obsessed with authority, blind to social reality, copes with increasingly elaborate power plays

- Kenneth the Page: Obsessed with TV and helping, blind to exploitation, copes with more enthusiasm

The framework is universal because it mirrors how real people work. We all have obsessions, blind spots, and coping mechanisms. Comedy characters just have them turned up to eleven.

From Understanding to Application

Once I understood the three-pillar framework, my character writing transformed. Instead of trying to make characters funny through dialogue or situations, I built engines and let them run.

The best part? When you have well-built engines, they write themselves. Put Patricia and Kevin in a room together, and their obsessions will clash. Their blind spots will prevent resolution. Their coping mechanisms will escalate the conflict. You don’t need to force funny situations – the characters create them naturally.

That’s the real magic of character comedy. Once you build the engine, all you have to do is turn it on and watch it go.

Leave a Reply